Sometime around the year 1000, Kahoolawe was settled by Polynesians, and small, temporary fishing communities were established along the coast. Some inland areas were cultivated. Puʻu Moiwi, a remnant cinder cone, is the location of the second-largest basalt querry in Hawaii, and this was mined for use in stone tools, such as koʻi. Originally a dry forest environment with intermittent streams, the land changed to an open savanna of grassland and trees when inhabitants cleared vegetation for agriculture & firewood. Hawaiians built stone platforms for religious ceremonies, set rocks upright as shrines for successful fishing trips, and carved petroglyphs (drawings) into the flat surfaces of rocks. These indicators of an earlier time can still be found on Kahoolawe. While it is not known how many people inhabited Kahoolawe, the lack of freshwater probably limited the population to a few hundred people. As many as 120 people might have once lived at Hakioawa, the largest settlement, which was located at the northeastern end of the island—facing Maui.

Violent wars among competing ali’i laid waste to the land and led to a decline in the population. During the War of Kamokuhi, Kalani’opu’u, the ruler of the Big Island, raided and pillaged Kahoolawe in an unsuccessful attempt to take Maui from Kahekili II.

From 1778 to the early 19th century, observers on passing ships reported that Kahoolawe was uninhabited and barren, destitute of both water and wood. After the arrival of missionaries from New England, the Kingdom of Hawaii under the rule of King Kamehameha III replaced the death penalty with exile, and Kahoolawe became a men’s penal colony sometime around 1830. Food and water were scarce, some prisoners reportedly starved, and some of them swam across the channel to Maui to find food. The law making the island a penal colony was repealed in 1853.

A survey of Kahoolawe in 1857 reported about 50 residents here, about 5,000 acres of land covered with shrubs, and a patch of sugarcane growth. Along the shore, tobacco, pineapple, gourds, pili grass, and scrub trees grew. Beginning in 1858, the Hawaiian government leased Kahoolawe to a series of ‘ranching’ ventures. Some of these proved to be more successful than others, but the lack of freshwater was a relentless obstacle. Through the next 80 years, the landscape changed dramatically, with drought and uncontrolled overgrazing deteriorating much of the island. Strong trade winds blew away most of the topsoil, leaving behind red hardpan dirt (a trademark of the Hawaiian islands today).

From 1910 to 1918, the Territory of Hawaii designated Kahoolawe as a forest reserve in the hope of restoring the island through a ‘revegetation and livestock removal’ program. This program failed however, and leases again became available. In 1918, the rancher, Angus MacPhee of Wyoming, with the help of the landowner Harry Baldwin of Maui, leased the island for 21 years, intending to build a cattle ranch there. By 1932, the ranching operation was enjoying moderate success. After heavy rains, native grasses and flowering plants would sprout, but droughts always returned. In 1941, MacPhee loaned part of the island to the U.S. Army, who would later acquire the entire island during the War in the Pacific after the events at Pearl Harbor.

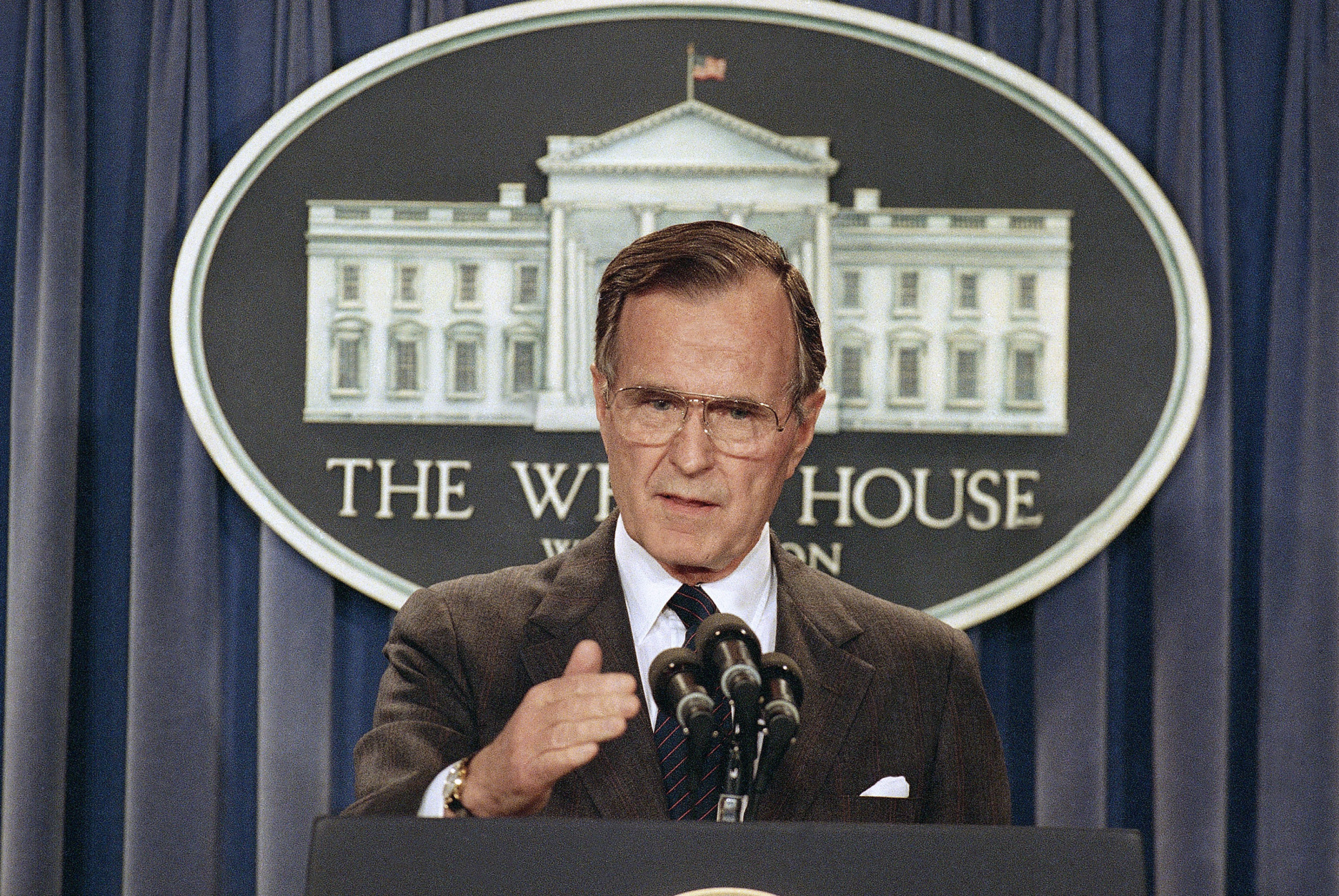

The use of Kahoolawe as a bombing range was believed to be critical, since the United States was executing a new type of war strategy in the Pacific Islands. Their success depended on accurate naval gunfire support that suppressed or destroyed enemy positions as U.S. Marines and soldiers tried to get ashore. Use of the island as official training grounds would continue until 1990 when George H.W. Bush ordered an end to the use of the island for military & navel training via the Kahoolawe Island Conveyance Commission, which was responsible for recommending terms and conditions of conveyance of Kahoolawe from the U.S. Gvovernment to the state of Hawaii.